"For me, quality is in the endurance of a piece of jewellery so it looks good when you buy it and stays looking good over a long period of time."

How did you come to be chief engraver at The Royal Mint (TRM)?

I studied maths, physics and chemistry, then decided that I was more interested in art but I’ve still got that technology and science knowledge in the background. Once I made the decision that I was going to be creative, I trained as a jeweller. After my degree, I got involved in some competitions designing medals for TRM and it went from there: I got a job as a trainee with a plan of staying three years… and nearly 30 years later I’m still there.

How is the new 886 by The Royal Mint jewellery collection built on your skills and TRM’s age-old techniques?

As technology has advanced, the way we apply our craftsmanship in terms of coins has changed. Whereas I was trained to hand engrave and to cut dies [moulds for machine-pressing] in steel with basic hand tools, now we’re more likely to design using CAD [computer aided design software] and the tools are cut with lasers.

Moving back into jewellery is in some ways a step back in technology: back to hand skills, back to craftsmanship, back to individually handling every single item that we produce rather than just letting the machines do it. But what we’re trying to do is leverage our minting skills to develop jewellery in a way that is idiosyncratic to us. We’ve got kit that no normal jeweller would have so we’re leveraging our knowledge, skills and equipment to make jewellery that’s better quality in terms of forming the pieces. Then we’re going back to hand skills to finish, polish and assemble every piece.

Coins have to be incredibly durable; are you bringing that to the jewellery?

Yes, one of the pitfalls of casting, which is the main production method for most jewellery these days, is that it’s inherently weak. There’s porosity: there are cavities within it, which mean that it’s brittle, it’s liable to break, it’s generally soft. Whereas with the minting technology that we apply, we squeeze pieces with massive tonnages so there is no porosity; the metal is very dense and very hard so it tends to have a better quality finish and also to be more resilient.

What exactly does it mean that the jewellery is “struck”?

“Striking” in coining is basically hitting it with a hammer. Although the “hammers” nowadays are presses that squeeze with a maximum capacity of 1,600 tonnes, that idea of compressing the metal either by squeezing it or hitting it is still the same. Striking gives the best results: it is very accurate and it does wonders for the metal in terms of compacting it and making it denser. But in order to strike pieces you need to manufacture very complicated, high quality tools for every design.

How have you had to adapt your manufacturing processes from coins to jewellery?

It’s a challenge because some of the things that [886 by The Royal Mint creative director] Dominic Jones would like to do in design are very difficult to do in terms of manufacturing so we’ve always got that positive tension between design and our manufacturing, which we are keeping in the UK to make the actual quality – not the appearance because it’s easy to make something look high quality – better. For me, quality is in the endurance of a piece of jewellery so it looks good when you buy it and stays looking good over a long period of time.

Do your manufacturing capabilities at TRM dictate what you can create?

Yes, my role is to develop our capability to manufacture Dominic’s designs. Over time we’ll develop the balance between pure design and design for manufacture. As with coins, there’s always a trade-off: things that are beautiful are not always the easiest to make but we don’t want to compromise on either. The product will speak for itself, I hope.

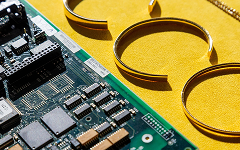

Tell us how 886 by The Royal Mint is making gold more sustainable.

You’d think all gold would be recycled because it’s so valuable but there is a lot going into landfill from electronic waste: mobile phones, computers and so on. [A record 54m tonnes of e-waste was generated worldwide in 2019, according to the UN’s Global E-waste Monitor report.] The gold we’re using is recovered from e-waste and we’re recovering it in a more environmentally friendly way. Traditionally all that e-waste was shipped to east Asia and burnt in a furnace to recover the gold, which is an extremely polluting and hazardous way to do it. We’re using a chemical process that has very few byproducts, which is a much more economic and ecologically friendly way of extracting gold. The fact that this is landfill turned into beautiful objects is really interesting for me.

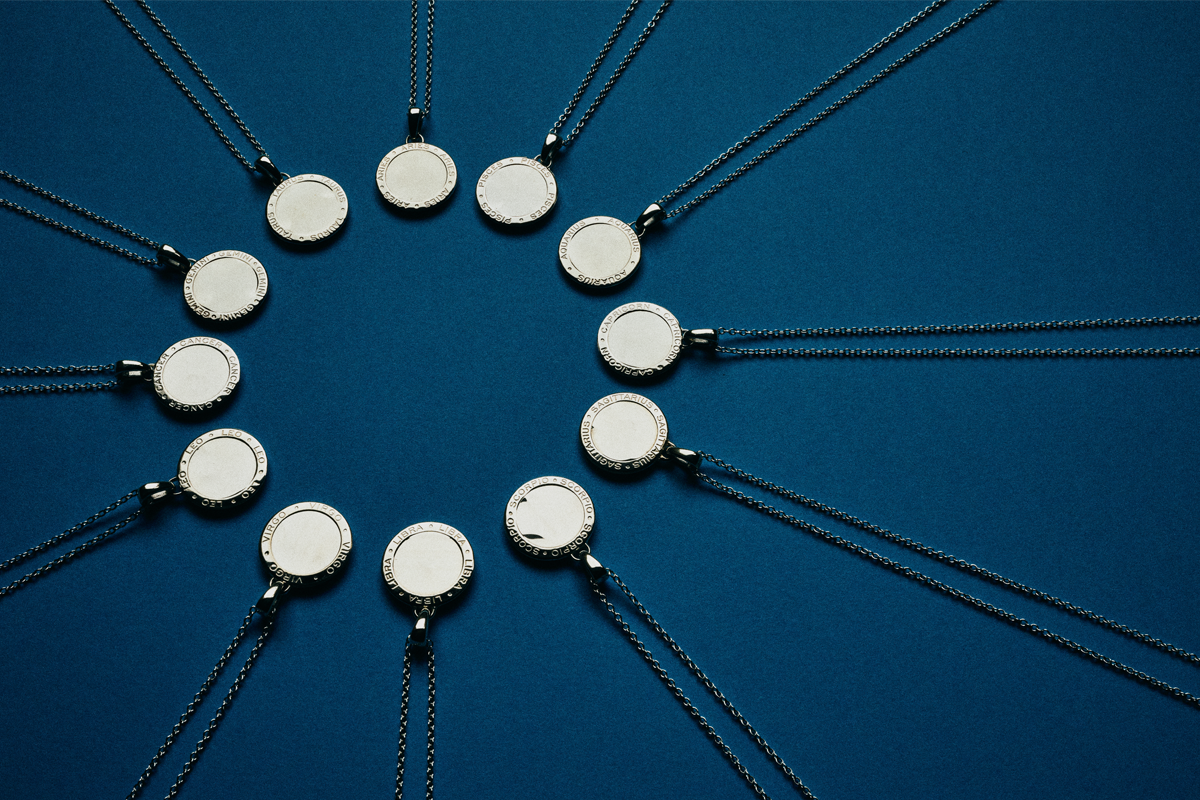

What will consumers notice about 886 by The Royal Mint jewellery that is unique to TRM?

The relationship with bullion is key to 886 by The Royal Mint. It’s about retaining value as an asset so some design elements will indicate how much gold is in them. The quality should be apparent. For example, we’ve worked really hard to make earrings with a positive feedback noise so when you close them they make a clear clicking sound.

When we’re talking about quality and durability, it isn’t just about the look of it; it’s about functionality as well. We’re hoping to make jewellery that people love to wear, that become heirloom pieces. If people love to wear them, they’re going to get worn, not just sit in a drawer so they have to last.